Design Principles

Dependency Inversion Principle in C# – SOLID Design Principles – Part 5

Overview

In our introduction to the SOLID Design Principles, we mentioned the Dependency Inversion Principle as one of the five principles specified. In this post we are going to discuss this design principle. Though a discussion of Dependency Injection and Inversion of Control are warranted here, we will save those topics for another post. I want to discuss the Dependency Inversion principle as simply and directly as possible.

Dependency Inversion Principle – Introduction

The Dependency Inversion Principle is a software design principle that provides us a guideline for how to establish loose coupling with dependencies from higher-level objects to lower-level objects being based on abstractions and these abstractions being owned by the higher-level objects.

The definition reads as follows:

- High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. They should both depend on abstractions.

- Abstractions should not depend upon details. Details should depend upon abstractions.

These two items state that when building software, classes should be loosely-coupled based on abstractions (interfaces) and the details of the implementation should be encapsulated within the concrete classes that contain the logic. From top-down perspective, higher-level classes have only loose dependencies with lower-level classes.

What does that mean?

Dependency Inversion is about reversing the standard and conventional direction of dependencies from higher-level objects to lower-level objects by ensuring that the interfaces that dictate the functionality of the lower-level objects (i.e. the contracts that mandate what the lower-level objects must do) are owned by the higher-level objects. After all, if we consider our software holistically, the higher-level orchestrating objects are more valuable than the lower-level objects because they are the objects whose functionality we are most likely going to have the desire or need to extend.

Because the interfaces (contracts) that define what but not how the lower-level objects function are owned by the higher-level consumers, the higher-level objects do not rely upon how a lower-level object provides its functionality. Instead, they define what they need the lower-level objects to do and the lower-level objects provide the functionality/behavior demanded.

What Problems Are Solved with Dependency Inversion?

Poorly written software that is difficult to maintain and that has too many “hard” dependencies is a nightmare! How many times have we seen objects with numerous dependencies that cause us to shy away from trying to make changes? In my career I have seen more than I would care to remember!

When proper design principles are not considered early in the process, we often end up with code that is a tangled web of dependencies and when we are forced to make changes we often encounter unforeseen breakages that occur because of these dependencies.

When we implement the Dependency Inversion Principle, we reduce the coupling between “pieces” of code. When we build dependencies based upon interfaces (contracts), we introduce greater stability over time and we reduce the “hard” dependencies from concrete class to concrete class. Thus we reduce the possibility of introducing instability over the course of time. By coding to interfaces, we force our implementing classes to honor their agreements while the objects that consume them have no need to know how they honor them.

When we build software components that are reusable and consumable and that have external dependencies, we can find great value in the Dependency Inversion Principle’s objectives.

A word of caution – we cannot just program to interfaces and say that we have implemented Dependency Inversion! I will admit that this is a great idea in and of itself but by itself it does not give us Dependency Inversion. To truly realize the benefits, we have to ensure that the interfaces we use are owned and controlled by the higher-level objects. In other words, the top-level consumers own the contracts that must be honored by the lower-level providers.

So, using interfaces alone is NOT Dependency Inversion! Using interfaces to define what is needed by higher-level objects and writing lower-level objects to provide those needs by honoring the needs of the consumers in a way that the consumers have no reason to know anything about how the lower-level objects do what they do is moving in the right direction.

It is reasonable to say that classes are always going to have dependencies on other classes. You just can’t have properly-built object-oriented software without having dependencies between classes. But when changes are needed, it is very advantageous to make sure that changes have minimal impact on the overall functionality of the classes with dependencies on the classes changed. When we have tight coupling between classes, it is difficult to do this.

Let’s consider two types that we all know – an Engine and a Starter. We can say that an Engine has a dependency on a Starter as shown in the diagram below.

If we assume here that every Engine has a Starter that’s a pretty reasonable assumption. We can say that when we instantiate an Engine object we must also create a Starter object to start the Engine. With this model, the two are tightly-coupled.

But what if we have to change the starter and replace it with a different one? What if we have to change something in the Starter class? Such a change could potentially break the functionality of the Engine. How can we prevent that?

First, let’s make a statement: an Engine requires a component that is able to start it. It does not specifically require a Starter. With this in mind we can begin to decouple the two. Look at the next design with the understanding that the dotted gray line signifies ownership and control of types:

We’ve created an IStarter interface and since the Starter class implements this we are in good shape, right? Not exactly. Yes, the Engine having a dependency on the IStarter interface is an improvement since any class that implements IStarter can be used but we don’t have a hard dependency on Starter. We are moving in the right direction but we’re not there yet!

Let’s think about this from the standpoint of Dependency Inversion. To invert the dependency, the higher-level object must define and control the interface. Think about this: what if the Starter object changed in a way that forced a change to the IStarter interface? That could potentially break the Engine class’s logic because although it only expects a type that implements IStarter, the IStarter interface does not belong to the Engine class and is not defined based on what it needs. Therefore, the perceived loose coupling here is not real because the higher-level object (Engine) does not truly have control over the IStarter interface.

To implement Dependency Inversion, the higher-level modules must have control over the interfaces that they use to define their requirements for lower-level objects. Let’s revisit our logical design this way:

Now we’re getting somewhere! The Engine class owns the IStarter interface and thus controls what the classes that implement IStarter must provide. Nice! With this scenario, a change to a class that implements the IStarter interface that changes the interface is not valid.

So where is the inversion? If we go back to the first Engine/Starter diagram above, we see that changes within that scenario bubble from the bottom up. Changes to lower-level components force changes to higher-level components. With our new design, since the higher-level component owns and controls the interface, any change in the lower-level component that breaks its interface implementation is not valid unless the higher-level object allows it and the IStarter interface is changed as well. If the Engine must be changed in a way that affects the IStarter interface, the forcing of change is top down. In other words, the Starter must be changed as a result of a mandated change by the Engine. Make sense?

Another Example of Dependency Inversion

Let’s look at a simple example to which we can all relate. Think about the electric appliances in your house. They all have voltage requirements. In the U.S. we generally have 110, 220 and in some cases 440-volt power. If you’ve ever noticed, the plugs for each voltage are different.

In the context of Dependency Inversion, we can think of an appliance as a higher-level consumer and of the power supply in our house as a lower-level object that provides functionality needed by the appliance to operate. The appliance defines and owns its defines its needs and publishes those needs via its physical plug “interface”.

Though this sounds overly simple, it is a valid example of Dependency Inversion. So when we have an appliance that requires 220-volt service and we plug it into a 220-volt outlet, we expect for it to just work. We know that the plug is capable of providing 220-volt power because (1) the plug on the wall matches the plug on the appliance, and (2) the receptacle and wiring were put in place by a licensed electrician who knows and understands the electrical codes and the functional requirements of any device that uses 220-volt power. In other words, they power supply honors the “contract” between it and any device or appliance manufactured to use it.

From a software development perspective, we can say that the appliance is the higher-level object, the power cord and plug are the contract that defines what is needed by the higher-level object, and that the power supply itself is the lower-level object that is capable of honoring the needs of the consumer. We know that it can provide the needs of the consumer because in this case the physical characteristics of the receptacle (wall plug) tell us that it “implements the proper interface”. We can even say that the plug/receptacle connection is an abstraction. The appliance has no need to understand how the receptacle provides 220-volt power just that it does.

Refactoring Our Original Engine/Starter Design Sample

Now that we have covered Dependency Inversion and considered a couple of simple examples, let’s now return to the Engine/Starter design to which we’ve been applying SOLID design principles over the past few posts.

To recap this design, way back in the first post on the Single Responsibility Principle (Part 1) we originally started with a simple design that represented an Engine and its dependency on a Starter to provide ignition functionality. Our first design looked like this:

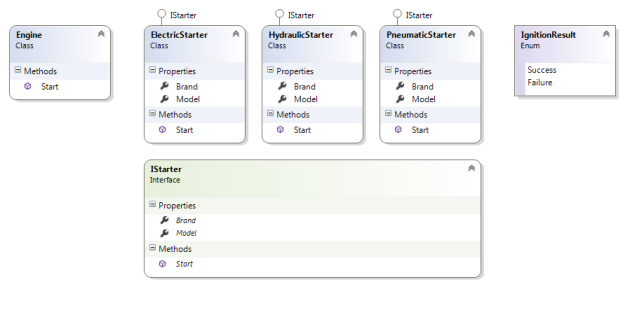

Then, in the second post on the Open-Closed Principle (Part 2) we refactored the design to make it open to extension but closed to modification. In the original design, we identified the three types of starters to be electric, pneumatic, and hydraulic. Because the implementation details of each unique type of starter were so different, we moved from a single Starter type to distinct types for each. We then created an interface named IStarter that they all implemented.

Due to the fact that each starter type had internal functionality that was so different, to ensure that our derived (implemented) classes being substitutable for their base types (or interfaces), we segregated our interfaces as we see below. You can refer back to these posts for more information – Liskov Substitution Principle (Part 3) and Interface Segregation Principle (Part 4).

Our starting code looks like this:

namespace SOLIDDesignPrinciples

{

#region Base Classes

public class Component : IComponent

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

}

#endregion Base Classes

#region Interfaces

public interface IComponent

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

}

public interface IStarter : IComponent

{

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public interface IElectricStarter : IStarter

{

Battery Battery { get; set; }

}

public interface IPneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

AirCompressor Compressor { get; set; }

}

public interface IHydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

HydraulicPump Pump { get; set; }

}

#endregion Interfaces

#region Starter Types

public class ElectricStarter : Component, IElectricStarter

{

public Battery Battery

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : Component, IPneumaticStarter

{

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : Component, IHydraulicStarter

{

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

#endregion Starter Types

#region Starter Support Components

public class Battery : Component

{

public bool IsCharged

{

get

{

/*we could write logic here to handle the

validation of the battery's charge

for now, we will just return true */

return true;

}

}

}

public class AirCompressor : Component

{

}

public class HydraulicPump : Component

{

}

#endregion Starter Support Components

#region Enums

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

#endregion Enums

}

Basically, this code representation of the different types of Starter types required to fulfill the ignition functionality for an Engine type can be summarized as follows:

- There are three distinct types of Starters – ElectricStarter, PneumaticStarter, and HydraulicStarter.

- Each Starter type implements the IStarter interface which defines the properties that are common to all Starter types, and each implements its specific interface type. The specific interface type is necessary because each type of starter is unique in its own operational requirement(s).

- The IStarter interface implements the IComponent interface.

- Each Starter type inherits the Component base class and each Starter interface implements the IStarter interface.

- The lower-level components required by the Starter types also inherit Component (since they are components too).

If we include the Engine itself in our dependency chain, we have a clear dependency hierarchy. Let’s look at it from an abstraction standpoint:

- Engine has a dependency on a Starter, or rather anything that is an IStarter.

- An IStarter can be an IElectricStarter, IPneumaticStarter, or IHydraulicStarter.

- An IElectricStarter has a dependency on a Battery.

- An IPneumaticStarter has a dependency on an AirCompressor.

- An IHydraulicStarter has a dependency on a HydraulicPump.

Hold on a minute! Weren’t these supposed to all be abstractions? Yes they were, so let’s take a look at the lower-level objects and do some further decomposition.

If we are going to build dependencies based on abstractions all the way down the chain, we need to think a little more about what I will call the second-level objects. In the case of a Battery, in reality there are about five distinct types of automobile batteries! So to provide a proper abstraction from the ElectricStarter to a Battery, we must make this dependency an abstraction too.

If we refer to this resource, we lean more about our previous statement that there are five distinct types of car batteries – just check it out if you are interested :). To be correct in our design and to make our code as closed to modification as possible, we must define each type as a distinct type within our design. These distinct types will then be set as dependencies of the ElectricStarter abstractly.

To do this, we first make the Battery class an abstract base class.

public abstract class Battery : Component, IBattery

{

public bool IsCharged

{

get;

set;

}

public abstract void EvaluateCharge();

}

We made the EvaluateCharge() method abstract to force our derived Battery classes to override its functionality.

We are also going to create specific battery type classes and although the actual logic behind how to validate the battery’s charge may vary significantly based on the type of battery, each type must still offer the EvaluateCharge() functionality. Make sense?

So here are our new classes for each type of battery:

public class WetFloodedBattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class CalciumCalciumBattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class VRLABattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class DeepCycleBattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class LithiumIonBattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

If you look at these classes and say “they’re all the same!”, yes they are. Imagine that the charge validation logic is very different for each distinct type. That logic is not the point of this example, so we are not touching that. For this sample, all of the overridden methods just set the IsCharged property value to true 🙂 We have segregated each distinct type to honor the Single Responsibility Principle and give our classes only one reason to change. You can refer back to that post if you would like.

Next, to keep things simple, we have made our ElectricStarter class generic. When we create a new instance of an ElectricStarter we will have to inject an IBattery type into the constructor. This way we are using Constructor Injection to inject the ElectricStarter’s battery dependency upon creation. We will cover Dependency Injection in another post, so don’t get stuck on what we just said here. Just understand that we are requiring every instance of an ElectricStarter to be supplied with an instance of an IBattery type.

Let’s take a look at our new ElectricStarter class:

public class ElectricStarter<T> : Component, IElectricStarter<T>

where T : IBattery

{

public ElectricStarter(T battery)

{

this.Battery = battery;

}

public T Battery

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

this.Battery.EvaluateCharge();

if (this.Battery.IsCharged == true)

{

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

else

{

return IgnitionResult.Failure;

}

}

}

We should also note that we have made our IElectricStarter interface generic.

public interface IElectricStarter<T> : IStarter

{

T Battery { get; set; }

}

So far so good. Now let’s return to our Engine class and make some changes.

First, we will make the Engine.Start() accept the IStarter instance.

public interface IEngine : IComponent

{

IgnitionResult Start(IStarter starter);

}

#endregion Interfaces

#region Engine

public class Engine : Component, IEngine

{

public IgnitionResult Start(IStarter starter)

{

return starter.Start();

}

}

#endregion Engine

If we then flip over to the Program.cs class of our sample C# Console application, and add code to instantiate an Engine, a starter, and a battery and run it we will see a successful engine start!

namespace SOLIDPrincipleSamples

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

IEngine engine = new Engine();

IBattery battery = new LithiumIonBattery();

IElectricStarter<IBattery> starter = new ElectricStarter<IBattery>(battery);

IgnitionResult result = engine.Start(starter);

}

}

}

So now that we have defined this design, are working with dependencies based on abstractions, and have an Engine that we can start, let’s consider the ownership of the interfaces we have defined from a Dependency Inversion standpoint.

First, remember that the higher-level objects must own the interfaces. If we consider our model from the top down, we start with the Engine.

The Engine depends on a Starter, or more appropriately an IStarter. Since we created interfaces for each of the three types of starters (IElectricStarter, IPneumaticStarter, IHydraulicStarter) the Engine should own and have control over those interfaces.

Each type of Starter has a dependency on some lower-level object. In the case of the ElectricStarter, there is a dependency on a Battery, or should we say an IBattery. As we built our code we discovered that there are actually five different kinds of car batteries and we created classes for each and each class implemented the IBattery interface. Therefore, the ElectricStarter should own the IBattery interface. We could go so far as to say that the Engine could conceivably own it as well and that would not necessarily be wrong, but we want to segregate ownership where it truly belongs.

If you want to create your own C# console application and play with this a little more, the code for the Engine, starters, and all other classes/interfaces is below. You can copy and paste this into a single .cs file if you want and experiment.

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

namespace SOLIDDesignPrinciples

{

#region Base Classes

public class Component : IComponent

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

}

public abstract class Battery : Component, IBattery

{

public bool IsCharged

{

get;

set;

}

public abstract void EvaluateCharge();

}

#endregion Base Classes

#region Interfaces

public interface IComponent

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

}

public interface IStarter : IComponent

{

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public interface IElectricStarter<T> : IStarter

{

T Battery { get; set; }

}

public interface IPneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

AirCompressor Compressor { get; set; }

}

public interface IHydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

HydraulicPump Pump { get; set; }

}

public interface IBattery : IComponent

{

bool IsCharged { get; set; }

void EvaluateCharge();

}

public interface IEngine : IComponent

{

IgnitionResult Start(IStarter starter);

}

#endregion Interfaces

#region Engine

public class Engine : Component, IEngine

{

public IgnitionResult Start(IStarter starter)

{

return starter.Start();

}

}

#endregion Engine

#region Starter Types

public class ElectricStarter<T> : Component, IElectricStarter<T>

where T : IBattery

{

public ElectricStarter(T battery)

{

this.Battery = battery;

}

public T Battery

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

this.Battery.EvaluateCharge();

if (this.Battery.IsCharged == true)

{

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

else

{

return IgnitionResult.Failure;

}

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : Component, IPneumaticStarter

{

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : Component, IHydraulicStarter

{

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

#endregion Starter Types

#region Starter Support Components

public class WetFloodedBattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class CalciumCalciumBattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class VRLABattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class DeepCycleBattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class LithiumIonBattery : Battery, IBattery

{

public override void EvaluateCharge()

{

//logic here to evaluate the charge

this.IsCharged = true;

}

}

public class AirCompressor : Component

{

}

public class HydraulicPump : Component

{

}

#endregion Starter Support Components

#region Enums

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

#endregion Enums

}

Points to Ponder

One more thing to think about with Dependency Inversion is how abstraction is handled within the various layers of an application or object hierarchy. I have written numerous application frameworks in my time as an architect and developer, and one thing that holds true when writing this type of code is that you find yourself within the various levels writing abstract code with the intent of it being used concretely at some later point in time. It is necessary to rely upon generic abstractions within lower levels and allowing the ultimate consumers/clients to determine the exact implementation details. With Dependency Inversion, we can effectively build objects that perform the necessary tasks without knowing the exact details of each task at the time we write them. This idea may sound a bit counterintuitive at first, but it is something to think about as you explore this topic more deeply.

Additional Links

The SOLID Design Principles

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Single Responsibility Principle in C# – SOLID Design Principles – Part 1

Overview

In our introduction to the SOLID Design Principles, we mentioned the Single Responsibility Principle as one of the five principles specified. In this post we are going to dive into this design principle with a very simple example in C#.

The Single Responsibility Principle states that a class should have only one reason for change. The greater the number of responsibilities, the more reasons a class will have for change. Seems pretty simple, right? When you consider it for what it is, it is pretty simple.

I am most definitely NOT a mechanic, and I do not claim to know a great deal about combustion engines, but I think that a subset of an engine’s functionality is a great way to illustrate the SOLID design principles. The engine in your automobile is a marvel of modern engineering and has been designed to function optimally with each component having minimal dependencies on other components. An engine is maintainable because the various parts/components are easily removed and replaced. This is how our applications should be written.

So let’s consider an automobile engine from the standpoint of the starter mechanism. In case you don’t know, your engine has a component called a starter that is attached to the engine, has electrical connections to allow it to draw power from the battery, and when you engage your ignition switch via a key or pushbutton, the starter is energized. When it is energized, it forces the engine to turn over and the combustion process begins. If you would like to learn more about how a starter works, here is a great article 🙂 Haha. So let’s move on, shall we?

IMPORTANT: For the sake of simplicity, we are going to assume that for this example, the one hard rule that will not ever change is the fact that there will always be a Starter object and a Battery object associated with an Engine. If we don’t make this assumption and declare it as a “rule”, the scope of our design changes could make the illustration of the concept overly-complicated and I really want to keep it simple here and discuss the principle in the simplest terms possible.

Furthermore we are going to use our design in this post to continue to apply SOLID design principles one by one.

Design #1 – Not so Good

Let’s suppose that we wanted to represent an Engine’s ignition/starter functionality in a few C# classes. If we didn’t understand the Single Responsibility Principle, we might build our classes similarly to this:

Based on the design shown above, let’s consider this code:

public class Engine

{

public IgnitionResult Start(Starter starter, Battery battery)

{

//we would put code here to handle the logic for checking

//whether or not the batter is charged

//then we check the result of our logic

if (battery.IsCharged)

{

//we could put logic here to handle

//the actual ignition process

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

else

{

//uh oh! the battery is not charged

//Failure!

return IgnitionResult.Failure;

}

}

}

public class Starter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

}

public class Battery

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public bool IsCharged

{

get;

set;

}

}

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

Let’s think about this code as it is written. It makes sense that we would have an Engine class, a Starter class, a Battery class, and an IgnitionResult enum. So far so good. But when we look in the Engine class and read the Start() method, we can see that there may be more than one reason why the Engine class would have to be changed. It is responsible for too many things. Any logic associated with how to start the engine is contained within the Start() method as is the “validation” of determining whether or not the battery is charged.

Consider the following questions:

- What if we installed a different type of Battery and the logic associated with verifying its charge state changed?

- What if we installed a different type of Starter and the logic associated with how it actually works internally changed?

If either of these things changed we would have to modify our Engine class to accommodate the change(s). The key point here is that the Engine class has more than one responsibility and per the Single Responsibility Principle this is not good.

Design #2 – Better!

Now let’s reconsider our design, remembering that each class should have not more than one reason for change.

First, the logic for actually handling the Starter’s ignition process should be moved to the Starter class and the Starter itself should contain a Start() method which will be invoked by the Engine’s Start() method.

Next, the battery charge validation logic should be moved to the Battery class since the battery itself knows better than anything how to validate its own state. Sounds sensible, right?

Let’s take a look at the improved design:

So what did we do? First, we removed anything to do with the “internal workings” of the Starter and the Battery out of the Engine class and into each respective class. Now, based on the assumption we made above that stated in this scenario an Engine will always have exactly one Starter and exactly one Battery, the Engine class has only one reason for change as do the Starter and Battery classes.

Keep in mind that as we get into the other SOLID Design Principles we are going to begin abstracting things so that we will have a truly “pluggable” design but for now we are working directly with concrete Starter and Battery objects. That will change as we move through the other principles and we will begin to see continuous improvement!

We left the Brand and Model properties in the Starter and Battery classes. Obviously we can see that this is not an ideal design, but remember – we are focusing on the Single Responsibility Principle for now! These properties are inconsequential now.

Based on the design shown above, our new code looks like this:

public class Engine

{

public IgnitionResult Start(Starter starter, Battery battery)

{

return starter.Start(battery);

}

}

public class Starter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start(Battery battery)

{

//since the Battery class now contains that actual charge validation

//logic, the Starter merely checks the value of that property

//and the Battery takes care of the rest

if (battery.IsCharged)

{

//we can put the ignition logic here

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

else

{

return IgnitionResult.Failure;

}

}

}

public class Battery

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public bool IsCharged

{

get

{

//we can put logic here for the battery

//to validate its charge and return

//a result

return true;

}

}

}

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

So we have a better design from the standpoint of the Single Responsibility Principle. The goal is to modify all of our classes so that each class has one and only one reason for change. Since the example is very simple, accomplishing this is pretty easy. As designs become more complex, the amount of time to create the correct design can grow tremendously but the time required is very well worth it long-term because it will yield a much more maintainable and effective design overall.

In the next post, we will dive into the Open-Closed Principle. See the links below for all posts related to the SOLID Design Principles.

The SOLID Design Principles

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Open-Closed Principle in C# – SOLID Design Principles – Part 2

Overview

In our introduction to the SOLID Design Principles, we mentioned the Open-Closed Principle as one of the five principles specified. In this post we are going to dive into this design principle and work with a very simple example in C#.

The Open-Closed Principle states that modules should be open for extension but closed for modification. Simply stated, this means that we should not have to change our code every time a requirement or a rule changes. Our code should be extensible enough that we can write it once and not have to change it later just because we have new functionality or a change to a requirement.

If you consider the number of times that code is changed after an application makes its first ‘release’ and you begin to quantify the actual time (and expense) associated with repeated changes to code over the life of the application, the actual development cost is probably not going to surpass the ongoing maintenance costs.

Think about it, when you change existing code, you have to test the changes. We all know that 🙂 But to be complete in your implementation, you also have to perform regression testing to ensure no unforeseen bugs have been introduced either as direct or indirect results of your new changes! In short, we don’t want to introduce breakages as the result of modifications – we want to extend functionality.

But let’s be realistic for a second. To interpret the Open-Closed Principle to say that we can NEVER change our code is a bit over-the-top in my opinion. I can tell you from years of practice that this is simply never going to happen! There will always be code changes as long as there are requirements changes – that’s just the way it is. You can however greatly minimize the actual code changes needed by properly designing applications in the beginning, and the Open-Closed Principal is one of the five SOLID design principles that allow you to do that.

In the last post, we began building a few classes that represent the starter/ignition system of an automobile engine. As is the theme for all posts here, we kept the example scenario very simple and kept the code simple to illustrate the design principle.

We are going to take the code that we wrote in the Single Responsibility Principle post and modify it further to illustrate the Open-Closed Principle. We have removed the Battery class because in the context of this discussion it is really not significant and introduces unnecessary noise.

So let’s get going! For more background on how we arrived at the design below, refer back to the the previous post.

The code looks like this:

public class Engine

{

public IgnitionResult Start(Starter starter)

{

return starter.Start();

}

}

public class Starter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//logic to initiate start

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

Let’s consider this design, and also consider the two notions described by the Open-Closed Principle. Modules that conform are:

- Open for Extension – the behavior can be extended in a variety of ways as the requirements change

- Closed for Modification – existing, stable code should not be changed

With these things in mind, let’s discuss what we need to do with our Engine/Starter scenario to allow us to minimize changes going forward.

Open-Closed Principle – C# Example

So to get started, let’s take the code from the last post (shown above) and add a little meat to it! We purposely left the body of the Start() method of the Starter class kind of bare because we weren’t concerned with that when we discussed the Single Responsibility Principle. But now we are very interested in that so let’s add a StarterType enum, a StarterType property to our Starter class, and let’s add some dummy logic within the Start() method to make this all work. Remember, this initial code is NOT going to adhere to the Open-Closed Principle – we are modifying the original code in preparation for this.

Design #1 – Not so Good

First, we will add the StarterType enum:

public enum StarterType

{

Electric,

Pneumatic,

Hydraulic

}

Then we will add a property to the Starter class:

public StarterType StarterType

{

get;

set;

}

Finally, we will add some logic to our Starter class’s Start() method that performs some action based on the StarterType specified.

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//initiate the starter based on the StarterType

if (this.StarterType == SOLIDPrincipleSamples.StarterType.Electric)

{

//initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

else if (this.StarterType == SOLIDPrincipleSamples.StarterType.Pneumatic)

{

//initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

else

{

//initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

Okay, we know that we could have one of three types of starters – electric, pneumatic, or hydraulic. Seems reasonable that we would write an if block that checks the type and performs some type of action, right? Well, not really. What if our requirements change and we have to now accommodate another type of starter that we hadn’t anticipated? Well, we will have to change our Starter class, and we really don’t want to do that!

So what can we do?

Design #2 – Much Better

The solution is actually pretty straightforward and it involves thinking in terms of extending NOT modifying! Here’s how we can do that:

First, let’s rethink our Starter class. Instead of having a single concrete Starter class, we will create a concrete class for each type of starter and consider each as a distinct type within our design. To bring all those together, we will create an interface which we will name IStarter. Each of our three starter types will implement this interface and each will contain its specific logic for initiating the engine start functionality.

Our new design looks like this:

So here are our new classes and our new interface:

public class Engine

{

public IgnitionResult Start(IStarter starter)

{

return starter.Start();

}

}

public interface IStarter

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public class ElectricStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

So now we have three concrete classes, one for each type of starter, a single interface which is implemented by each of the three concrete starter classes, and our StarterType enum is no longer needed! With this design, if we need to add a new type of Starter, we do NOT have to change our existing code but instead we can add a new class for that type of starter and change the consuming code very slightly to expect the new type where needed. We are not going to dive into a Factory pattern in this post, but that is an effective way to handle the Open-Closed Principle.

So to recap, if we write code that is open for extending but closed to modification we are much better off! The Open-Closed Principle provides us guidance for how to accomplish this. Now keep in mind that this was a simple example, but as I say all the time, simple examples are the best ways to illustrate virtually any development topic.

In the next post, we will dive into the Liskov Substitution Principle. See the links below for all posts related to the SOLID Design Principles.

The SOLID Design Principles

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Liskov Substitution Principle in C# – SOLID Design Principles – Part 3

Overview

In our introduction to the SOLID Design Principles, we mentioned the Liskov Substitution Principle as one of the five principles specified. In this post we are going to dive into this design principle and work with a very simple example in C#.

As you study the SOLID Design Principles, you will notice there is a great deal of overlap among the individual principles. While discussing the Liskov Substitution Principle, we are going to take a quick dive into the Interface Segregation Principle as well, but not overly so as the next post will discuss that more deeply. We will however take a look at how to segregate interfaces in pursuit of not violating the Liskov Substitution Principle.

Formal Definition

The Liskov Substitution Principle states that if for each object m1 of type S there is an object m2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when m1 is substituted for m2 then S is a subtype of T.

Useful Definition

Let’s reword the definition above to actually be understandable. In a nutshell, the Liskov Substitution Principle includes two main points:

- Derived classes should be substitutable for their base classes (or interfaces).

- Methods that use references to base classes (or interfaces) have to be able to use methods of the derived classes without knowing about it or knowing the details.

So what in the world does all that mean? It means that our derived classes (or implementing classes) cannot modify or break the functionality dictated by their base classes or implemented interfaces.

Let’s just dive in and take a look at the Engine/Starter class design that we have been using for the first two posts on the SOLID Design Principles.

As of the completion of our post on the Open-Closed Principle, here is our design:

We created separate concrete classes for the different types of Starters used to start our Engine and we made each class implement the IStarter interface. This allowed us to migrate our code to be open to extending but closed to modification.

So far so good, right? Well, maybe not!

Let’s look at the code from the last post that matches the class diagram above:

public class Engine

{

public IgnitionResult Start(IStarter starter)

{

return starter.Start();

}

}

public interface IStarter

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public class ElectricStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

Design #1 – Not Good At All!

This all works fine in the simple example because we are assuming that all types of Starters are the same. But what if they aren’t? What if, for example an ElectricStarter makes use of a Battery, a PneumaticStarter makes use of an AirCompressor, and a HydraulicStarter requires a HydraulicPump object to function? Well, if we were hell-bent on keeping our IStarter interface we could do something like this:

First we would have to create classes for Battery, AirCompressor, and HydraulicPump. Then we would add properties for each to the IStarter interface. Let’s just do it and see how it looks 😦

public interface IStarter

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

Battery Battery { get; set; }

AirCompressor Compressor { get; set; }

HydraulicPump Pump { get; set; }

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public class ElectricStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public Battery Battery

{

get;

set;

}

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An Electric Starter does not use an AirCompressor.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An Electric Starter does not use an AirCompressor.");

}

}

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An Electric Starter does not use a HydraulicPump.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An Electric Starter does not use an HydraulicPump.");

}

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public Battery Battery

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An PneumaticStarter does not use a Battery.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An PneumaticStarter does not use an Battery.");

}

}

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get;

set;

}

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An PneumaticStarter does not use a HydraulicPump.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An PneumaticStarter does not use an HydraulicPump.");

}

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public Battery Battery

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("A HydraulicStarter does not use a Battery.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("A HydraulicStarter does not use an Battery.");

}

}

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("A HydraulicStarter does not use an AirCompressor.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("A HydraulicStarter does not use an AirCompressor.");

}

}

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class Battery

{

}

public class AirCompressor

{

}

public class HydraulicPump

{

}

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

Alright! So we added the properties to our IStarter interface and implemented them in each concrete class, so all is well, right? Not exactly.

Although we aren’t necessarily violating the Open-Closed Principle, we are in violation of the Liskov Substitution Principle and honestly this is just really not a good design! Although we implemented all of the possible properties of our classes in our IStarter interface, the classes that implement our interface are NOT substitutable for it. Why not? Because their behavior is not consistent across the different types of starters. Although the interface is in place, the implementing classes don’t truly implement it when in play.

Consider this: suppose we create an instance of an ElectricStarter and use an instantiated Battery object to set its Battery property? That works pretty well. But now let’s imagine another developer consuming our code and seeing the Compressor property as being a usable public property for the ElectricStarter and trying to either get it or set it. What happens? A NotImplementedException is thrown 🙂 This is not consistent behavior! The interface contains a property for an AirCompressor, a developer consuming our code can reasonably expect that to work, despite the fact that any of us “reasonable” people might look at that and ask “why would an ElectricStarter need an AirCompressor?” 🙂

So you may ask “why not just remove the NotImplementedExceptions in the properties that don’t matter for each class and just go with it?” The answer to that is easy – any time you see properties or methods within derived (or implementing) classes that do not do what their name suggests (or what they should be doing) that is a big red flag or a not-so-good design! As responsible designers/developers, we must handle invalid conditions and operations correctly and deliberately and not place properties or methods in our interfaces or classes that surprise their consumers by what they do or how they behave – make sense? Thus instead of having a property or method that actually does nothing is not a good idea and the presence of such items signals trouble!

The Liskov Substitution Principle is very focused on extrinsic public behavior and the fact that consumers expect predictable and constant behavior for published/implemented interfaces. Our design does NOT provide that!

Design #2 – Much Better

To rectify this flawed design, we need to think about another SOLID design principle – the Interface Segregation Principle. If we think about our IStarter interface as the starting point, we can consider the following things:

- The properties/method that are common to ALL starter types are: Brand, Model, and Start().

- The properties that are specific to each starter type are: Battery, Compressor, and Pump.

With these things in mind, the first thing that we need to do is to make use of not one interface but four! Take a look at our revised interfaces below:

public interface IStarter

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public interface IElectricStarter : IStarter

{

Battery Battery { get; set; }

}

public interface IPneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

AirCompressor Compressor { get; set; }

}

public interface IHydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

HydraulicPump Pump { get; set; }

}

I picked the interface segregation as our starting point because it sets the stage for the changes that need to be made to the concrete classes. This design is far superior from the standpoint of the Liskov Substitution Principle!

So now let’s rewrite our Starter classes to implement their respective interfaces:

public class ElectricStarter : IElectricStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public Battery Battery

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : IPneumaticStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : IHydraulicStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

We now have a design that makes far more sense. Yes, we went from one interface to four, but this is not a bad thing when we consider the SOLID Design Principles collectively, which is a very good thing to do.

In the next post, we are going to dive more deeply into the Interface Segregation Principle. See the links below for all posts related to the SOLID Design Principles.

The SOLID Design Principles

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Interface Segregation Principle in C# – SOLID Design Principles – Part 4

Overview

In our introduction to the SOLID Design Principles, we mentioned the Interface Segregation Principle as one of the five principles specified. In this post we are going to dive into this design principle with a very simple example in C#.

In the last post on the Liskov Substitution Principle, we utilized the Interface Segregation Principle to refactor our code. The code that we write in this post will be very simple as well and will take that code and introduce another segregation of our interfaces. I generally do not write posts that are “recaps” of previous posts, but our implementation from the last post certainly warrants a “recap” in this one.

The Interface Segregation Principle states that clients (classes) should not be forced to implement interfaces that they do not use. Well this certainly sounds reasonable, doesn’t it?

So if we start with our original design from the Liskov Substitution Principle post, here is our original design and code:

public class Engine

{

public IgnitionResult Start(IStarter starter)

{

return starter.Start();

}

}

public interface IStarter

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public class ElectricStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

In our last post, instead of a single Starter class, we created a distinct type for each type of Starter – electric, pneumatic, and hydraulic. Then we realized that in actual implementation, each type of starter had a different requirement for the object it used to actually work. The ElectricStarter utilized a Battery, the PneumaticStarter utilized an AirCompressor, and the HydraulicStarter utilized a HydraulicPump. When we actually wrote the code needed to make these work, we realized that our single interface just did NOT make sense. See the code below.

public interface IStarter

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

Battery Battery { get; set; }

AirCompressor Compressor { get; set; }

HydraulicPump Pump { get; set; }

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public class ElectricStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public Battery Battery

{

get;

set;

}

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An Electric Starter does not use an AirCompressor.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An Electric Starter does not use an AirCompressor.");

}

}

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An Electric Starter does not use a HydraulicPump.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An Electric Starter does not use an HydraulicPump.");

}

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public Battery Battery

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An PneumaticStarter does not use a Battery.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An PneumaticStarter does not use an Battery.");

}

}

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get;

set;

}

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An PneumaticStarter does not use a HydraulicPump.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("An PneumaticStarter does not use an HydraulicPump.");

}

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public Battery Battery

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("A HydraulicStarter does not use a Battery.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("A HydraulicStarter does not use an Battery.");

}

}

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get

{

throw new NotImplementedException("A HydraulicStarter does not use an AirCompressor.");

}

set

{

throw new NotImplementedException("A HydraulicStarter does not use an AirCompressor.");

}

}

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class Battery

{

}

public class AirCompressor

{

}

public class HydraulicPump

{

}

public enum IgnitionResult

{

Success,

Failure

}

Upon reviewing this code more, it became painfully apparent that it was quite bad and required some refactoring. So, per the Interface Segregation Principle, we broke out the interfaces that we actually needed and went from one interface to four interfaces. As a result, each Starter class implemented its own interface that interface had only what was needed for that type. Nice! Our final code from the last post is below:

public interface IStarter

{

string Brand { get; set; }

string Model { get; set; }

IgnitionResult Start();

}

public interface IElectricStarter : IStarter

{

Battery Battery { get; set; }

}

public interface IPneumaticStarter : IStarter

{

AirCompressor Compressor { get; set; }

}

public interface IHydraulicStarter : IStarter

{

HydraulicPump Pump { get; set; }

}

We picked the interface segregation is our starting point because it sets the stage for the changes that need to be made to the concrete classes.

So then we rewrote our Starter classes to implement their respective interfaces:

public class ElectricStarter : IElectricStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public Battery Battery

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the electric starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class PneumaticStarter : IPneumaticStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public AirCompressor Compressor

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the pneumatic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

public class HydraulicStarter : IHydraulicStarter

{

public string Brand

{

get;

set;

}

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public HydraulicPump Pump

{

get;

set;

}

public IgnitionResult Start()

{

//code here to initiate the hydraulic starter

return IgnitionResult.Success;

}

}

And in doing that, we were introduced to the Interface Segregation Principle and used it to help us adhere to another principle. The overlap among the SOLID design principles is so nice!

In the next post, we are going to dive more deeply into the Dependency Inversion Principle. See the links below for all posts related to the SOLID Design Principles.

The SOLID Design Principles

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

SOLID Design Principles

In software development, principles differ from patterns in the sense that where patterns represent complete, identifiable, repeatable solutions to common problems, principles are objective, factual statements that can be made about code and the manner in which it is constructed and the overall design of an implementation. In other words, patterns refer to code scenarios while principles refer to qualities of code and these qualities are useful in identifying the value of the code.

In this post, we are going to be introduced to Bob Martin’s SOLID design principles. These principles have been around for a long time, and it is immeasurably important for every object-oriented developer to understand them and use them in making day-to-day design decisions. It is not that uncommon to see developers dive into development tasks by writing code first and considering architecture and design second. A good developer though inverts this scenario and considers a sound design before writing the first line of code! This prevents undue code maintenance pain later and allows for the development of better applications through and through.

Consideration of design principles is extremely important throughout a development effort, and failure to make the proper considerations can have a devastating effect on the development of the application and the application’s usefulness, performance, and maintainability.

What are the SOLID Design Principles?

In this section, we are going to outline and briefly discuss each of the five design principles. In subsequent posts we will dive into each principle in more detail. The five SOLID design principles are listed below:

- The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) – this principle states that there should never be more than one reason to change a class. This means also that a given class should exist for one and only one purpose.

- The Open-Closed Principle – this principle states that modules should be open for extension but closed for modification. This seems a bit unclear at first until you realize that you can change an object’s behavior by either using abstractions, implementing common interfaces, and from inheritance from common base classes or extending abstract base classes.

- The Liskov Substitution Principle – this principle, introduced by Barbara Liskov, simply-stated means that derivative classes have to be substitutable for their base classes. If we think about this for a minute, we can see that this also means that any class that implements a specific interface can be replaced by any other class that implements that interface. In other words, it can be substituted for the original class. Furthermore, a derived class must honor the ‘contract’ set by its super class.

- The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) – this principle states that objects should not be forced to implement interfaces that they do not use. Though this may sound obvious based on the wording, in practice it really means that interfaces should be finely-grained and not specific to the classes for which their implementation is intended.

- The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) – this principle states that higher-level classes should not depend upon lower-level classes but that both should depend on abstractions. Furthermore, these abstractions should not depend on concrete details but rather on abstractions as well.

Though each principle can be discussed individually, we should understand that no single principle should exist or be applied by itself. They should all be considered as part of the design process. In the following posts, we will dive into each principle in detail and take a look at some simplified code examples that illustrate each one.

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)